This week, we celebrated the feast of Saint Luke (who was thought to be a physician), and Peter graciously included a prayer for physicians at Compline. With the help of our son Andrew, who is a medievalist, I learned that physicians have been active on the Camino for 700 years. In the 14th century, the plague of Saint Anthony’s fire swept across Europe, and afflicted tens of thousands of pilgrims, especially the poor. The disease was caused by a fungus blight of rye grain that created boils, ulcers, gangrenous limbs, and even convulsions. The microbial origin of the disease wasn’t discovered until the 17th century, but the monastic order of the Hospitallers of Saint Anthony specialized in caring for pilgrims afflicted by Saint Anthony’s fire.

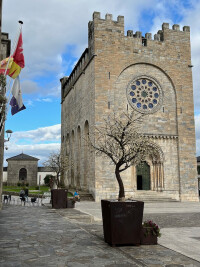

The three principal sites of pilgrimage in the middle ages were Rome, Jerusalem, and Santiago de Compastela. But in the 14th century (the time of Chaucers Pilgrims), the Saracens had retaken Jerusalem and the Papacy was an exile in Avignon. Thus, for reasons both secular and sacred, Santiago became the principal destination for pilgrimage and attracted tens of thousands of continental European travelers every year.

The monastic Antonines had been founded in the 12th century, specializing in the care of the victims of this particular plague. Although their understanding of its cause was imprecise, they knew that it was not infectious (unlike leprosy) and that poor nutrition contributed to its severity. The pilgrimage to Santiago could require more than two years of travel, and the diets of pilgrims were often unhealthy, particularly following a poor harvest when bread was often contaminated with the fungus.

There were more than 200 hospitals on the four roads to Santiago; at the hospital entrance pilgrims were screened to exclude infected lepers and to confirm the diagnosis of Saint Anthony’s fire. Once admitted, pilgrims received shelter for a week or more, wholesome food (with bread made from grain grown in mastic fields), analgesic ointment, and vasodilating medicine to prevent a gangrene, all free of charge. They were also expected to join in the monastic routine of prayers and liturgy in order to heal both body and soul.

The plague of Saint Anthony’s fire disappeared in the 17th century, but pilgrims today still require medical attention. I myself left our Parador in Villafranca del Bierzo in a wheelchair due to violent lower back spasms that required complete bedrest for two full days. (Thankfully, I am now once again upright and have recommenced walking with our group.) But bloody foot blisters remain a plague for pilgrims, even experienced hikers, prompting visits to the emergency room. Several of us today in Portomarin purchased hiking sandals to alleviate precisely this problem. The hospitallers of Saint Anthony may no longer be a monastic order, but we remain grateful to the doctors, nurses, pharmacies – and shoe stores – who enable us to continue on the Camino de Santiago.

I’ll close with part of Compline that we pray each evening and that has become such a source of solace and inspiration for our pilgrimage group:

“It is night after a long day.

What has been done has been done;

What has not been done, has not been done;

Let it be.

The night heralds the dawn.

Let us look expectantly to a new day,

New joys,

New possibilities.

In Jesus’ name we pray.

Amen.”